Moving from Australia to Taiwan was a significant transition this year, made even more challenging by the trauma I carried with me. Navigating this new chapter of my life, I found solace and healing in painting and drawing. These creative outlets became my coping strategy, helping me process trauma and adapt to my new environment.

Trauma is a multifaceted experience that affects individuals in various ways (CSAT-US, 2014). While Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) often dominates the conversation, it’s essential to recognize that people react differently, exhibiting a range of psychological and behavioral responses. Among these are resilience, post-traumatic growth (PTG), and avoidance coping strategies (Finstad et al., 2021).

Resilience is the ability to adapt and cope effectively despite adversity (Bonanno, 2004). Many individuals, while exposed to trauma, do not develop PTSD but instead show resilience, maintaining stable psychological well-being. This resilience can lead to personal growth, improved relationships, and a stronger sense of self (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004).

Post-traumatic growth, on the other hand, refers to positive psychological changes resulting from facing adversity (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). Some individuals view trauma as an opportunity for personal transformation, experiencing greater appreciation for life, enhanced personal strength, and deeper spiritual connections.

Avoidance coping involves efforts to suppress or distract oneself from distressing thoughts and emotions (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980). While this may provide temporary relief, it can hinder long-term emotional processing and recovery. These varied responses underscore the diversity of experiences and coping mechanisms following trauma.

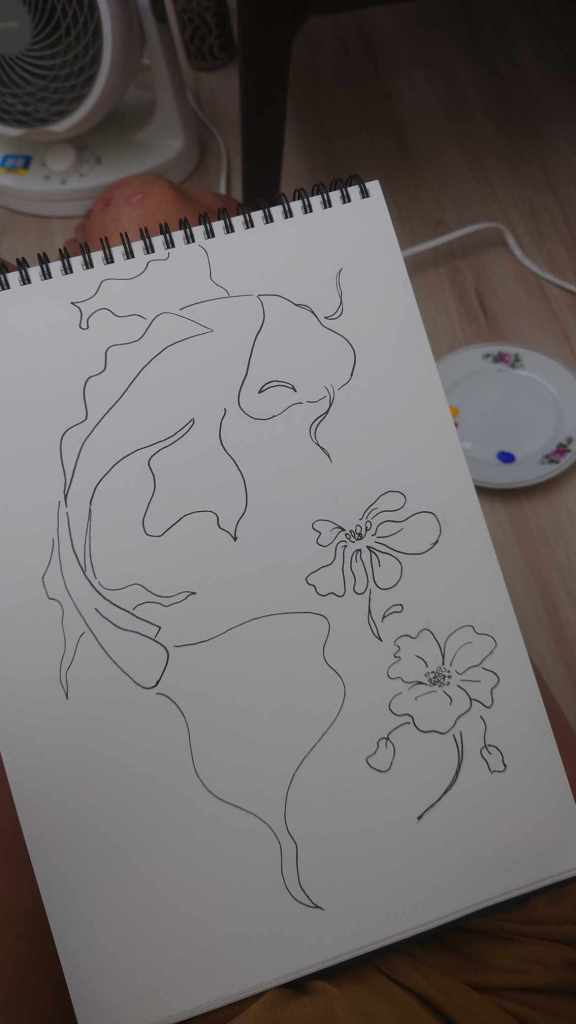

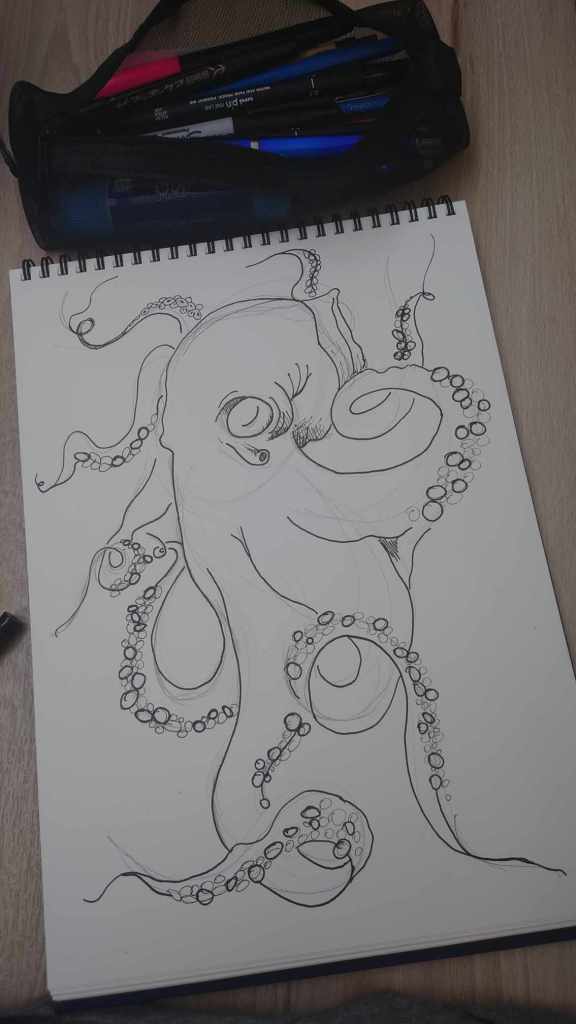

In my journey, painting and drawing have been vital tools for resilience and post-traumatic growth. These forms of visual art offer a non-verbal means of processing trauma and exploring inner experiences in ways that words often cannot (Magsamen & Ross, 2023; Stuckey & Nobel, 2010). High-stress situations, such as moving to a foreign country, have frequently sparked my creative inspiration. Since relocating to Taiwan, I’ve created numerous artworks that reflect my inner landscape and help me navigate my emotions.

Music has also played a crucial role in my self-care regimen. Growing up in a musically inclined household, with a mother who sings and dances and a father who sings and plays guitar, I naturally gravitated towards music as a form of emotional expression. Singing, playing the guitar, and composing music have provided an outlet for processing complex emotions associated with trauma (Magsamen & Ross, 2023; Silverman, 2012). For instance, during periods of grief, such as the passing of my grandmother, grandfather, and uncle, writing songs helped me cope and make sense of my feelings.

Engaging in these creative practices has been therapeutic, facilitating emotional release and self-expression. The therapeutic effects of art, as highlighted in “Your Brain on Art” by Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross, emphasize the power of creativity in high-stress situations. My drawings and paintings since moving to Taiwan illustrate this journey, capturing the profound impact of art on my ability to process and heal from trauma (Magsamen & Ross, 2023, p. 38; Malchiodi, 2012).

Through painting, drawing, and music, I’ve found a path to resilience and growth, transforming my trauma into a source of strength and creativity as I adapt to my new life in Taiwan.

References

Bonanno G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events?. The American psychologist, 59(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20

Bratman, G. N., Hamilton, J. P., & Daily, G. C. (2012). The impacts of nature experience on human cognitive function and mental health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1249, 118–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06400.x

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US) (CSAT-US). Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2014. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 57.) Chapter 3, Understanding the Impact of Trauma. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207191/

Finstad, G. L., Giorgi, G., Lulli, L. G., Pandolfi, C., Foti, G., León-Perez, J. M., Cantero-Sánchez, F. J., & Mucci, N. (2021). Resilience, Coping Strategies and Posttraumatic Growth in the Workplace Following COVID-19: A Narrative Review on the Positive Aspects of Trauma. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(18), 9453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189453

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An Analysis of Coping in a Middle-Aged Community Sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21(3), 219–239. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136617

Magsamen, S., & Ross, I. (2023). Your brain on art: how the arts transform us (First edition.). Random House.

Malchiodi, C. A. (2012). Handbook of art therapy. Guilford Press.

Silverman, M. J. (2012). Music therapy: An art beyond words. Routledge.

Stuckey, H. L., & Nobel, J. (2010). The connection between art, healing, and public health: A review of current literature. American Journal of Public Health, 100(2), 254–263.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Target Article: “Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence”. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.